exhibitions

-

Siwa Mgoboza | AFRICADIA | 17.11 – 20.12.2016

-

Cheikhou Bâ | MIGRATIONS | 12.01 – 15.02.2017

-

Cheadle & Erasmus | ANIMA ANIME | 09.03 – 11.04.2017

-

ANOMALIES | 20.04 – 22.05.2017

-

Hela Lamine | 24.05 – 26.06.2017

-

Ledelle Moe | CONGREGATION | RUPTURES | 23.06.2017

-

Ledelle Moe & Isabelle Merz | 29.06 – 02.08.2017

-

Florine Demosthene | THE UNBECOMING | 28.09 – 28.11.2017

-

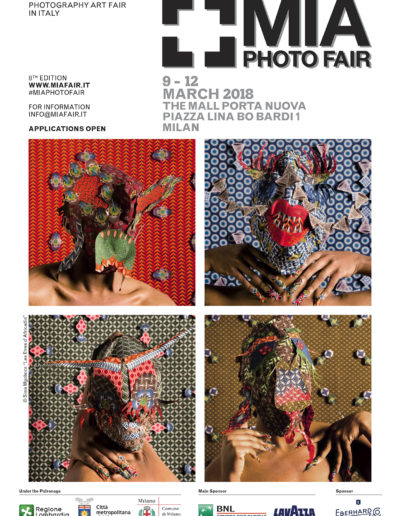

MIA Photo Fair | Milan | 08 – 12.03.2018

-

CONTIN[g]ENT @ Villa Dutoit | Geneva | 21.09 – 14.10.2018

Siwa Mgoboza | AFRICADIA | 17.11 – 20.12.2016

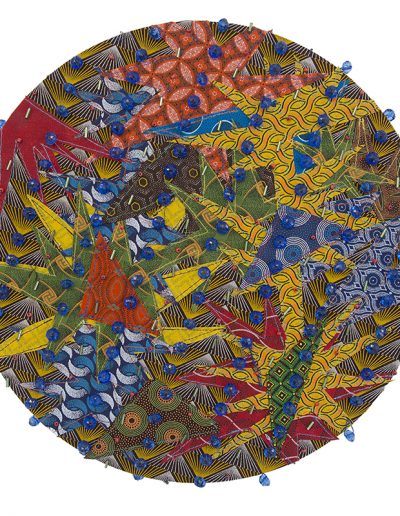

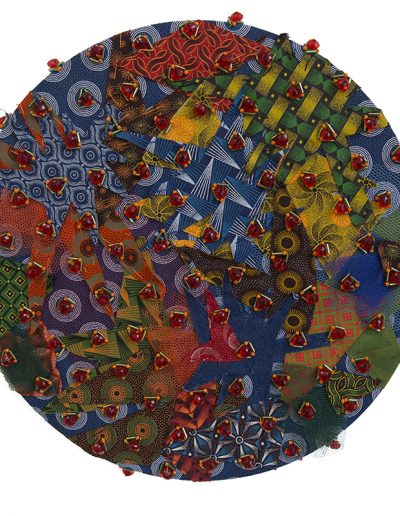

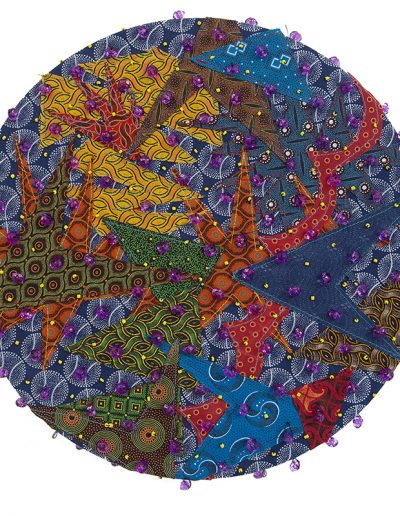

selected works from AFRICADIA:

What is AFRICADIA?

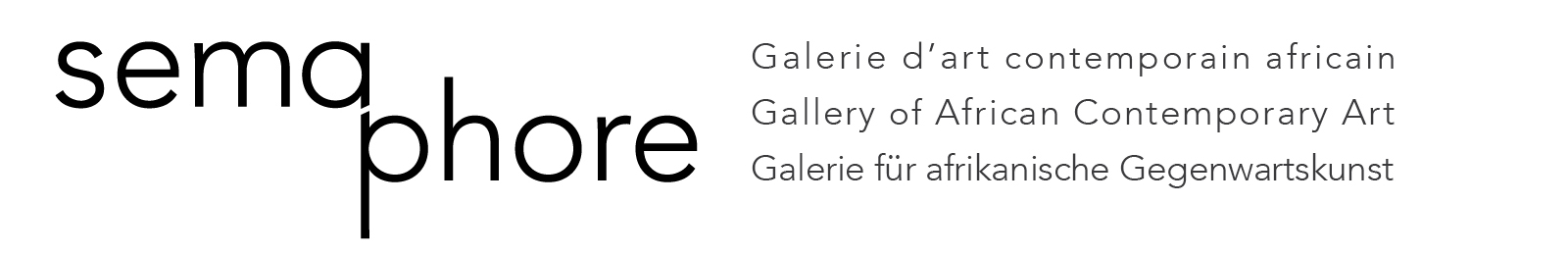

The work of South African artist Siwa Mgoboza examines the conflicts inherent in the globalised subject, within whom divergent cultural influences affect the sense of a unified self. Instead of looking to allay disparate cultural and political forces, Mgoboza plays them out against each other, his artworks becoming kaleidoscopic visions of multiple strands of identity.

Mgoboza has given a name to his vision of harmonious fragmentation: Africadia. Africadia is not a utopia – a non-existent place – but a symbolic ‘future land’ that can be achieved in political terms through tolerance and understanding.

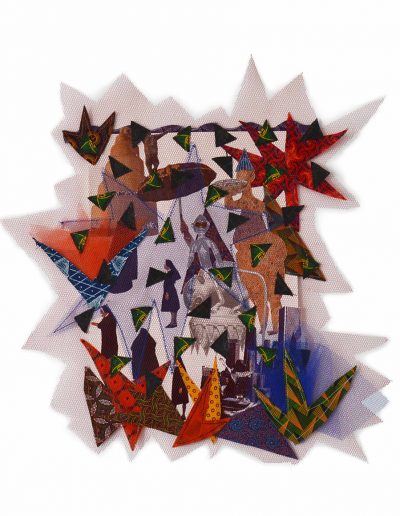

In the series Les Etres d’Africadia the culturally hybrid Beings are indistinguishable from each other in terms of race and gender. Mgoboza sets strips of highly coloured and patterned material alongside each other to create both the costumes for his beings and the settings they find themselves in, flattening the perspective and giving his hybrids and their backgrounds the same visual relevance.

The textile Mgoboza uses is a series of patterned cloths originally manufactured in Manchester at the height of the British Empire and later brought to South Africa by German and Swiss settlers. French missionaries presented bales of the cloth to King Moshoeshoe I, ruler of the Sotho. Possibly named for the king, Seshweshwe (or Isishweshwe, Shweshwe, iJermani or iDakkie) has been used for Sotho traditional wear since the 1840s. The type of indigo dye applied in the printing of the patterns was used as far back as the Bronze Age. At the time of colonial hegemony European countries used slave labour to cultivate the Indigofera plant in tropical territories. The production of cotton too, of which the cloth is made, has a history of forced labour and human subjugation. Today the textile is printed in South Africa but risks losing its market to cheap imports from Asia. The cloth symbolises shifting identity in a world where now, as then, conquest and domination exist alongside cultural exchange and trade.

Seshweshwe is also used in Mgoboza’s tapestries, where the fragmentation and juxtaposition of old forms and patterns create new, visually dynamic compositions.

In Who Let The Beings Out? one of Mgoboza’s Beings finds themself set against a background of traditional African artefacts and antiques. The creature as a new representative of Africa seems both out of and perfectly in place. There are strong tropes that unite the two worlds (the masks, for one) just as there are disparate elements that separate them (the vibrant colours set against organic shades).

Cheikhou Bâ | MIGRATIONS | 12.01 – 15.02.2017

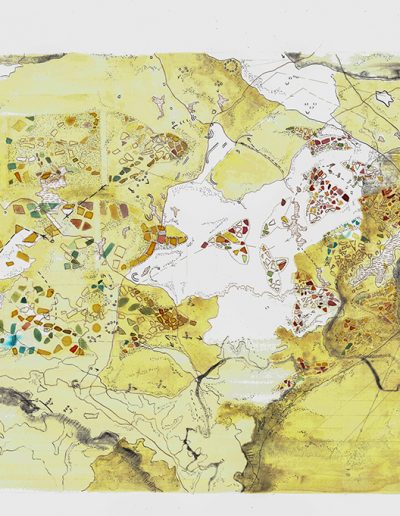

selected works from MIGRATIONS:

Why MIGRATIONS?

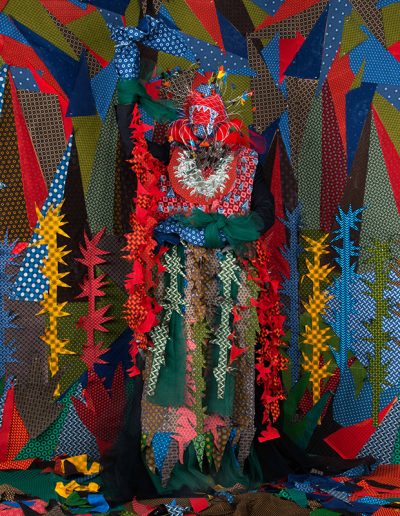

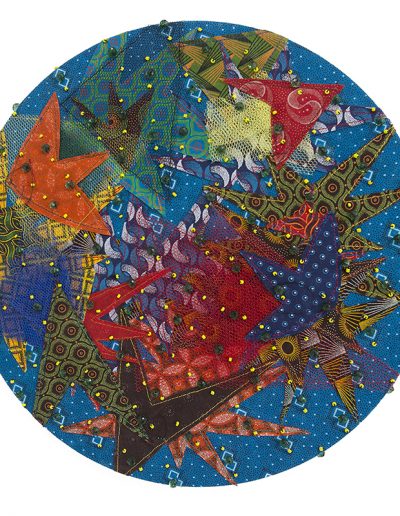

Cheikhou Bâ uses techniques such as collage and the application of bright colours on large-scale canvases to celebrate Migrations, the theme of his solo exhibition at Semaphore.

According to the Senegalese artist, migration – ’living beings moving from one point to another’ – is above all a ‘natural phenomenon’. The causes of these movements may be ‘conscious or instinctive’. Bâ highlights the role of instinct since he partly identifies the human desire to discover and populate other shores with the migratory movements of animals.

In a world divided by borders, human migration is restricted by policies that stop free movement, whether that movement is voluntary or automatic.

The artist points out:

Words such as emigration, immigration, exodus, exile could have associations of joy but more often than not are reminders of the unhappiness associated with migration.

However, Bâ’s work does not exemplify a critique of such policies but rather magnifies what is good about migration and its effects.

The paintings are ‘hybrid and mixed’ works. Strips of canvas and cardboard are juxtaposed and / or superimposed on the original structure. Bâ uses both oil and acrylic paints as well as markers such as chalk.

He explains:

All the paintings are made of mixed elements, different parts being grafted to the ‘original’ to enrich it and each other. This results in a kind of optical illusion that reminds one of uni-polyptychs.

Not polyptychs – works made of several distinct panels joined together – but ‘uni-polyptychs’: unified works assembled from multiple parts, whose diverse elements are difficult to differentiate from each other and divide into categories of belonging. This is analogous with modern societies enriched by migrations of all kinds, where individuals and communities are more than the sum of their separate identities.

The use of pointillism also references the theme of this series. The various-coloured particles are reminiscent of groups or crowds. In some paintings, bundles of bright dots wash up against areas of solid colour. Are these areas terrains that will be populated bit-by-bit, forbidden domains or hostile deserts? According to the artist, ‘beyond a purely compositional role, they are a representation of global demography and cartography.’

With this upbeat festival of colour and shape, Bâ could be one of those happy people he describes in the following terms: ‘[they] draw light from darkness, joy from bitterness, hope from loss [and create] equanimity in disappointment, generosity in destitution…’

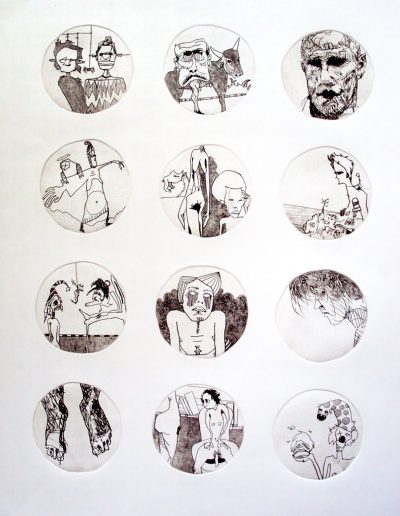

Cheadle & Erasmus | ANIMA ANIME | 09.03 – 11.04.2017

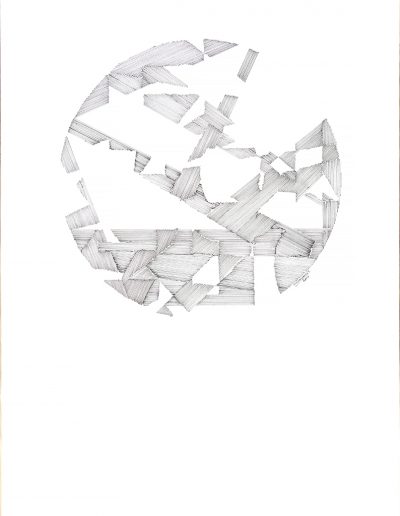

selected works from ANIMA ANIME:

Who are Jane Cheadle and Stephan Erasmus?

Jane Cheadle’s art does not deliver an overt political message but does reveal her interest in political theory, which she studied at the University of Cape Town before changing course. Her preoccupation with the concept of work, especially of precarious and manual labour and how it is organised, comes through in her art, in her acceptance of the transitory nature of what she creates as well as her approach to her materials.

By exploring the essence of the matter she uses for her art, she allows the ‘particular qualities of a given material to reveal themselves’. This ‘collaboration’ with the very stuff of fabrication occurred in the following way for the creation of Sharks (2007):

I spent quite a lot of time looking at that wood-patterned linoleum and then sliced it open. [It was] only when I discovered the beautiful grey concrete beneath that the idea started to emerge of cutting thin shapes and then placing them back. The thickness of the vinyl [,..t]he particular quality of that vinyl and how it was placed over concrete allowed for the animation to work. The form it took – sharks – was just a hunch or a dream, or perhaps inspired by the scalpel slicing. I knew it had to move ‘serpentine’.

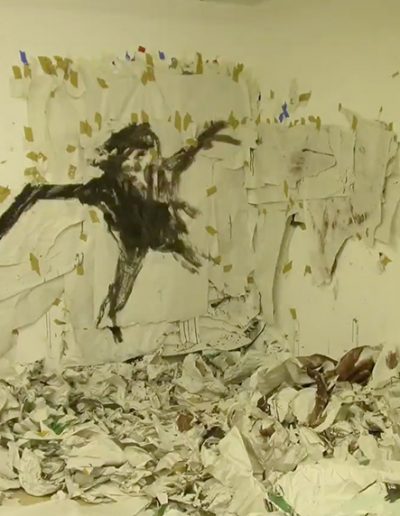

Another of her animations was made in a disused dance studio in Braamfontein, Johannesburg, in a building in which Cheadle and her collaborator, Cobi Labuschagne, had their studios. Because they were on friendly terms with the building’s cleaners, they were allowed into the dance studio at night for the duration of the project. Out of this clandestine arrangement grew Swimmer (2005), which won the Royal College of Art’s Man Group Drawing Prize in 2005. Paper becomes water as the swimmer, depicted not only in paint but also textile ink and food colouring, moves with great ease through an uncertain element.

Some of Cheadle’s animations are studies in reiteration and variation. At the beginning of Hope (2015) a round blackboard loses its white chalk coating as water runs over it. Unlike in Swimmer, where subsequent takes over a series of days at the end of the animation reveal the shadows of the artist and her collaborator, in Hope Cheadle’s stop motion keeps human agency in the background and the disc seems to turn on its own while spouting rivulets. The board rotates in one place but every movement creates new marks, patterns and strokes, as if an invisible hand were composing a quickly disappearing series of abstract paintings. The piece was entitled Hope based on the capacity of the circle to turn endlessly, although the squaring of the circle at the end of the animation does suggest that even hope can lose momentum.

Cheadle’s drawings have a fragile, transitory quality to them and they are created to be incomplete. They grow out of her animations or are creative preparation for them but are rarely stills from them. Although animation allows her to temporalise her drawing, her art is essentially about freedom, movement and transformation, with the latter encompassing deterioration as well as growth. As Cheadle states, ‘if something is fixed it has no potential for change’.

A versatile artist, Stephan Erasmus uses various media including, but not limited to, oil on canvas, watercolours, silkscreen, digital prints, book art, line drawings and sculpture in wood.

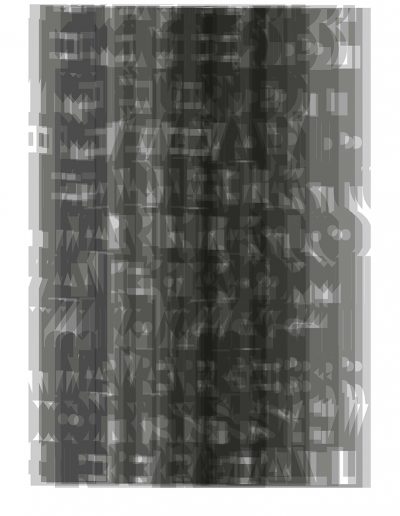

Erasmus treats text as a material and via the medium he adopts transforms it into visual art.

In the series Mist and Split and twisted, words are manipulated rhythmically to create pattern. The negative space between letters is given precedence in Line Drawings I to III and Text I to III Negative. Thread is stitched through letters punctured in paper in Threaded I and II.

In manipulating the text like a material Erasmus removes from it any capacity to instruct or inform. In Mist, the result of the working of the text is an obscuring veil. The text in Split and twisted has been woven into incomprehension and the threads hanging from the letters in Threaded I and II cloak any words.

In some of these series Erasmus uses five sets of texts from five short stories by Jorge Luis Borges as the basis for his visual manipulation. The Borges stories Erasmus has chosen deal with labyrinths, thus creating a ‘mise en abîme’: text in a visual form that renders it illegible and labyrinthine (Erasmus’ work) uses as its matter a legible text that explores the idea of a labyrinth in an – at times – surreal way that calls into question the very existence of material reality (Borges’ writing).

Some of Erasmus’ artworks make direct reference to coding and encryption. The artist will not give away the exact wording of the texts he manipulates. However, in the game of hide and seek there is always a tension between the desire to remain undiscovered and its opposite, the wish to be revealed. As Erasmus admits, ‘the hidden begs to be found.’ Yet he embraces the deflection and reflection his art engenders. Speaking of one of his pieces, he says, ‘each person who read [a] line of text started recognizing different words […] as people will recognize what is familiar to [them].‘

Erasmus has said of his art that it is a love letter to his muse. This muse is more often than not the Sophia of the gnostic tradition. Sophia is also a siren for Erasmus, ‘the muse who switches on the light of inspiration for a short period and then switches it off again so you have to struggle for a time.’ In another game of reflection Erasmus’ artwork is the embodiment of the light and shadow of his process of creation.

ANOMALIES | 20.04 – 22.05.2017

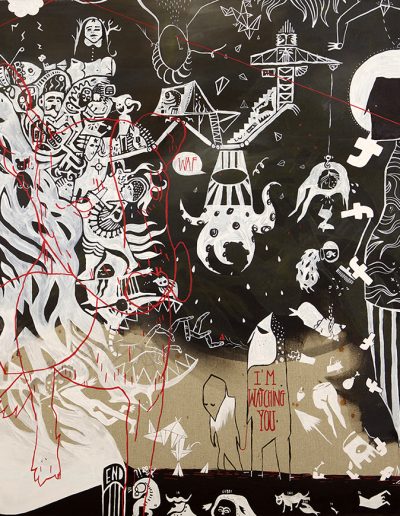

selected works from ANOMALIES:

Why are they ANOMALIES?

Vincent Bezuidenhout

South Africa

The apartheid regime, South Africa’s mode of government from 1948 to 1991, is the anomaly in Vincent Bezuidenhout’s series Separate Amenities. Bezuidenhout explains, ‘Recreational spaces previously functioned as separate facilities for different racial groups on every level of society, [and included] separate beaches, parks, walkways and swimming pools.’ This social engineering ‘led to spaces of ambiguity, incongruity and ultimate failure.’ Green Point Common, ATKV Playground, Kings Beach and Wild Waters show leisure areas or facilities that were ‘whites only’ zones.

Mandisa Buthelezi

South Africa

In Mandisa Buthelezi’s series Izithunzi zami the setting is not South Africa, as a cursory appreciation of the photographs would suggest, but France, where the artist had a residency in 2016.

Feeling out of place in a foreign country, she created photographs that speak ‘of the different shades of self and of history’ that make up a person. ‘Izithunzi zami’ is Zulu for ‘my shadows’, a reference to the ancestors, who, like shadows, may escape notice most of the time, even though they are always present. Her inward search for her identity results in an outward projection – the longed for country replaces the temporary, foreign place of stay. The French landscape, the anomaly in this body of work, is metamorphosed.

Tatenda Chidora

Zimbabwe

Tatenda Chidora chooses to treat unusual natural phenomena in human beings as things of beauty and photographs his subjects as glamorous models. The rarity of a phenomenon – a fleshy growth or a lack of melanin – makes it a paragon rather than an imperfection and draws the attention of the spectator to the aesthetic qualities intrinsic to it. The unusual is not the abnormal but the marvellous.

Matthew Kay

South Africa

Matthew Kay’s series The Front focuses on a space created in post-apartheid South Africa for the 2010 football world cup: the promenade on Durban’s beachfront. This body of work is a study of a zone that Kay thought he knew and understood but which became a strange and uneasy place once closely inspected. This ‘attempt at a truly integrated space’ has been a success to some degree since it ‘is a communal space that has regenerated Durban’s beach culture’ and ‘is unique in that it is free from many of the social constructs of other public spaces.’ However, Kay explains, ‘the old lines of segregation are lingering just below the surface’ while new socio-economic divides also become apparent within it.

Alice Mann

South Africa

Izangoma is a series by Alice Mann that portrays South African traditional healers. Westerners often refer to them as ‘witch doctors’, thereby, Mann believes, ‘perpetuating various misconceptions about traditional healers in contemporary African society’. They are often stereotyped as a throwback to ancient, primeval times and an anomaly in today’s world. Mann explains that ‘in many African cities [their] traditional practices have become seamlessly fused with modern and contemporary lifestyles’ and their work is understood ‘to compliment and promote modern ideals of health and wellness.’ The women portrayed here live in large cities and hold mid to high-level positions in conjunction with their roles as ‘izangoma’.

Siwa Mgoboza

South Africa

In his series Who Let The Beings Out? Siwa Mgoboza sets his contemporary creation, a being from the imaginary, future land of Africadia, against a backdrop of traditional African artefacts and antiques. At first glance this character, a new representative of Africa in terms of art and vision, seems out of place against the objects of an older, more traditional Africa. However, a closer reading of the images brings out the tropes that unite the two worlds: masks, performance and ceremony play important roles in both.

Mohamed Ouedraogo

Burkina Faso

In his series La carriere de granit Mohamed Ouedraogo visits a place that sits uneasily with our conception of the modern world: a stone quarry in the west of Ouagadougou, where men, women and children do heavy and dangerous labour to earn CFA 1 000 (approximately CHF 1.60) a day. ‘Here work and time do not have the same value as elsewhere,’ Ouedraogo states. The workers are in permanent danger of injury and breathe in an air filled with the smoke of burning tyres and the dust from broken granite. Some of them wear clothes that bear the logos and trademarks of a contemporary capitalist economy. The contrast is a cruel irony but perfectly symbolises the vast schism between the haves and the have-nots in a globalised society.

Simanga Zondo

South Africa

In his series of monochromatic self-portraits Simanga Zondo depicts inner states of mind that are not always considered ‘normal’ or ‘standard’. He highlights the pain of introspection as he sees it: an ‘act of looking into one’s own self and having to deal with inner unresolved issues and subjects.’ In this conversation with himself, he portrays mental states as physical events in a striking way.

Hela Lamine | 24.05 – 26.06.2017

selected works from Hela Lamine’s solo exhibition:

Hela Lamine's way of looking

Tunisian artist Hela Lamine presents for the first time in Switzerland works from her widely discussed exhibition The Unsecret Life of Samantha.C. The French publication L’OBS Rue 89 published the following explanation of this series: ‘Hela compiled everything she found [on the Facebook profile of SamanthaC.]: statuses, personal information, geolocation[s], but mostly 333 photos recorded over 34 months, from April 2014 to August 2015, when Samantha restricted access to her profile. It is from this material that Hela was inspired to create her graphic works’ (L’OBS, 13 November 2015).

After the process of creation had ended, ‘Hela sent a series of messages to SamanthaC, to Mark Zuckerberg, the CEO of Facebook, and the US Embassy in Tunis to explain her approach,’ wrote Psychologies Magazine in its 19-November-2015 issue. Lamine managed to talk to SamanthaC. about her work over Skype and invited her to the exhibition opening at the A. Gorgi Contemporary Art Gallery.

[An explanation by the artist of her approach can be seen in an interview on TV5Monde.]

Although this unusual initiative led to sermons in the press on the importance of protecting one’s privacy on social media, the meaning of Hela Lamine’s work lies beyond simple lessons. Admittedly, the Internet is an ideal place for the paired opposites of exhibitionism and voyeurism, openness and espionage, but the significance of the relation between the subject of a work of art and its creator has always been multiform. Such a relationship becomes even more complex when the viewer is added to the equation. Viewers have an even more privileged perspective since they observe the subject through the work while also observing what the work reveals of the artist.

This fusion of identities also occurs on another level. There is something inherently political in a Tunisian artist appropriating the personal performance of an American citizen. Not only is the subject American, but so too is the medium that allowed for so much of this harvested information to be shared carelessly or carefreely, depending on your point of view. The United States as spectacle, the United States permanently in the limelight, the United States as star of its own reality TV show – these are scenarios that are being played out today. The Tunisian artist appropriated a culturally specific demonstration intended for an American audience (real or imagined) and made it into something new. The result is reminiscent of the world in which we live, where the boundaries between the real and the virtual are constantly redrawn, where cultures are permeated by each other and where a subject becomes the arena for a play for ascendancy between various identities.

Hela Lamine has maintained contact with SamanthaC., whose full name was chosen before her Facebook profile as being representative of the everywoman. Little by little, after a first reaction of shock from the subject, trust has been established. The artist and her muse published a Facebook profile for this other Samantha C., a character constituted of them both, and plan to work together on a new project.

Lamine turns her slightly mocking – and sometimes openly derisive – gaze on her subject, SamanthaC., but this gaze also sweeps the artist herself, her loved ones and her private universe in her art. The exhibited works have been chosen from various periods to present Hela Lamine’s mischievous, playful and ironically questioning intelligence to a new audience.

Ledelle Moe | CONGREGATION | RUPTURES | 23.06.2017

selected views of the installation and performance:

Ledelle Moe's performance marking the 500th anniversary of the Reformation

South African artist Ledelle Moe was commissioned by the City of Neuchâtel to create an installation and performance piece to mark the 500th anniversary of the Reformation, a socio-cultural event that drastically changed the city and the region.

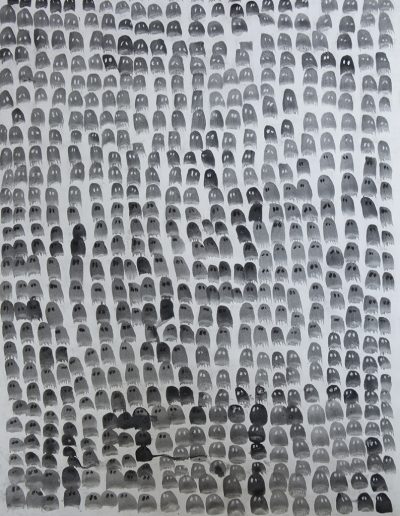

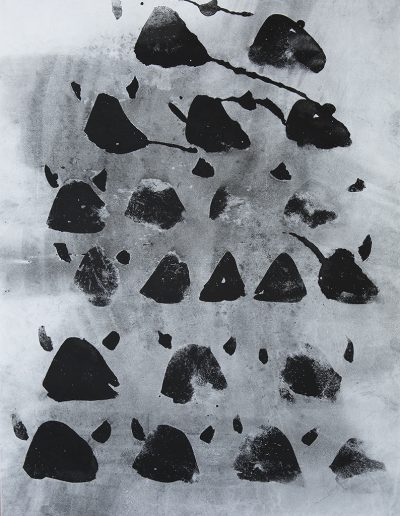

Moe moulded heads out of Neuchâtel soil mixed with cement, carving into the concrete once it had hardened to refine the shape. The heads would be used for both the installation on the statue of the reformer Guillaume Farel and for her performance piece.

‘Congregation’ is the name of the installation of unadorned heads on the shoulders, chest and back of the statue of Farel facing Neuchâtel’s Collégiale.

Moe covered the rest of the concrete heads in gold leaf for ‘Ruptures’, her performance. She assembled the heads on a metallic support to form a ‘cloud’ in front of Neuchâtel’s Collégiale. As the performance started, members of the public were asked to detach the heads from the support and to remove the gold leaf with steel wool, revealing the stark concrete beneath.

The participants’ actions brought to mind the destruction and renewal of the Reformation, the displacement of old symbols and icons and their reappropriation.

Local vocal artist Florence Chitacumbi sang as part of the performance.

Ledelle Moe & Isabelle Merz | 29.06 – 02.08.2017

selected works:

A two-woman exhibition

Ledelle Moe: Ruptures

Moe’s modus operandi is to create concrete sculptures that incorporate the soil of the place she is working in. The sculptor explains the significance of the process in the following way:

Experiencing the particular terrain of each site and creating work on that site [is] a way for me to engage intimately and physically with the very stuff of a place. In digging into the soil and quite literally using it as raw material in making my cement forms I [am] able to reflect on landscape as ground and to literally draw from it. Perhaps this [is] rooted in some longing to better understand how political and personal histories are inherent in the ever-present awareness of place. Or how ground, land, soil, and earth reference a sense of belonging.

During her stay in Neuchâtel, Moe produced a series of small heads in this way to be used in a performance commissioned by the city of Neuchâtel for its celebration of the five-hundred-year anniversary of the Reformation. The performance, which saw the artist and members of the public rub gold leaf from the heads to symbolise historical transformation in general and the rupture of the Reformed Church from the Catholic Church in particular, ties in with themes that Moe has been exploring for some time.

The new work is an extension of an earlier piece entitled ‘Congregation’, which was installed on a wall in a map-like formation. In ‘Ruptures’, the heads are arranged on a metal structure in what Moe calls a ‘cloud formation’. Moe imagines the heads drifting apart without the structure or being pulled inwards to a point of energy. Thanks to the framework, they have been suspended in space and time. In this frozen conversation, the relation of one head to another and of a single head to a group of heads can be examined at leisure. Moe’s scrutiny of the tension between the singular and the multiple, the individual and the group, the personal identity and the sense of belonging to a collective starts at the very beginning of the process of creation, when she sculpts each head individually from a mix of the ubiquitous, ‘plebeian’ material of cement with the local soil of a particular place, and runs through to the final installation of the heads in a group.

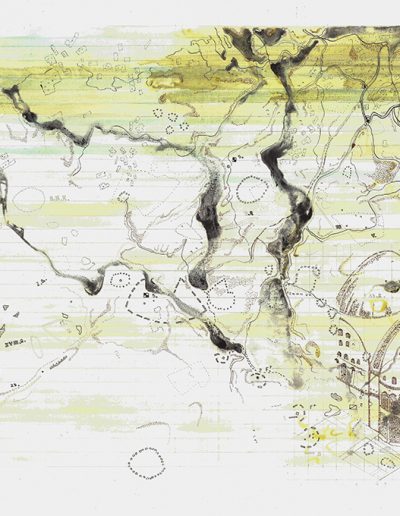

Isabel Mertz: Mea Culpa

Mertz’s work examines the concepts of home and the temporal qualities of place, and in so doing attempts to challenge and subvert patriarchal hierarchies in a poetic way.

In the series of drawings entitled ‘Mea culpa’, Mertz references ornate features found in sacred architecture and archival war manoeuvre graphs in such a way as to question their violent histories. By introducing deliberate errors in perspective and leaving rough marks from her initial drafting of the drawings – ‘through my fault (Mea culpa) – she creates ‘fault lines in the patriarchal narrative. As the artist explains, ‘These wholly subjective marks, along with a bird’s eye perspective which invites abstraction, reduce and fragment the intricate archival maps and architectural structures to redundant ornate gestures.‘

About Shrapnel, Mertz says:

The installation was inspired by a collection of tin toy soldiers my father collected during the Second World War in Germany. Grappling with these inherited objects and the patriarchal history they carry within them, I set out to manufacture works that were produced by repeatedly re-casting the soldiers in both tin and bronze until the original objects disintegrated.

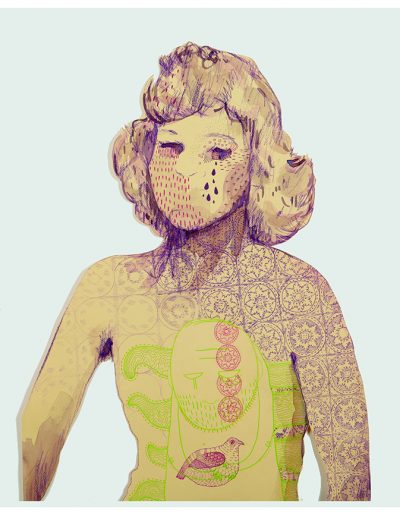

Florine Demosthene | THE UNBECOMING | 28.09 – 28.11.2017

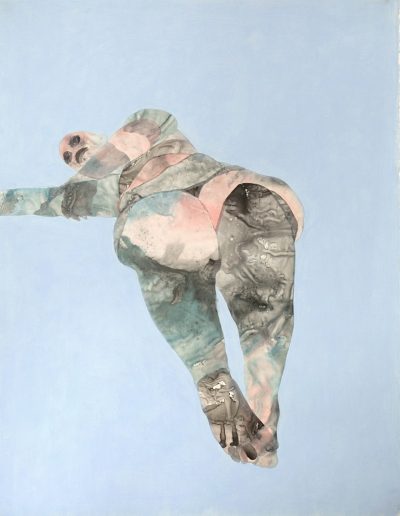

selected works:

What is THE UNBECOMING?

Florine Demosthene explores the concept of allure and the object of desire as a subject.

The artist challenges a Western ideal of beauty and its dictates, creating a black heroine who does not conform to stereotypes of the sensual nude. Demosthene’s heroine is not coy and openly defies viewers by staring back at them from several of the artworks. She is a very particular figure in terms of physical characteristics but also becomes a figurehead for the black female as a sexual and a self-defining being. This contemplation of the female nude as a being who is able to secure an identity of her own negates her role as a simple object of desire.

The heroine is entirely naked in some works, almost completely hidden in others, and in various stages of dress (or undress) in between these extremes. Demosthene sees her heroine as symbolically attired in cultural array. Her nakedness is the result of her attempts to remove these imposed coverings. ‘The cloths are the last vestiges of her past [;…] the heroine is wrestling with the past and present of her awakening,’ the artist explains.

Demosthene’s search for meaning in her rendering of her subject moves far beyond simple portraiture. For example, the skin of her heroine seems to be peeling away in certain paintings to reveal a mottled substratum of flesh. As the artist explains, her heroine has ‘un-become to come fully into who she is’ in her search for identity.

A new aspect in Demosthene’s work for The Unbecoming is the introduction of the Punu-Lumbo mask, usually found in the Ogooué River basin region of Gabon, which can represent female spirits and beauty. As Demosthene explains: ‘I use this mask as a sort of barrier between the real and the unreal and the seen and the unseen, much in the same way a masquerader delves between the realms of the human and spirit worlds.’

Demosthene has moved towards a palette of blues and greens, adding a new dimension to her existing palette of flesh colours, browns, oranges and ochre. This exhibition includes works of mixed media on the near translucent base of Mylar as well as even more recent collages on paper of mixed media on Mylar, where the latter’s layering creates an opaque effect. There are also mixed media pieces on canvas.

MIA Photo Fair | Milan | 08 – 12.03.2018

CONTIN[g]ENT @ Villa Dutoit | Geneva | 21.09 – 14.10.2018

Who was part of the CONTIN[g]ENT?

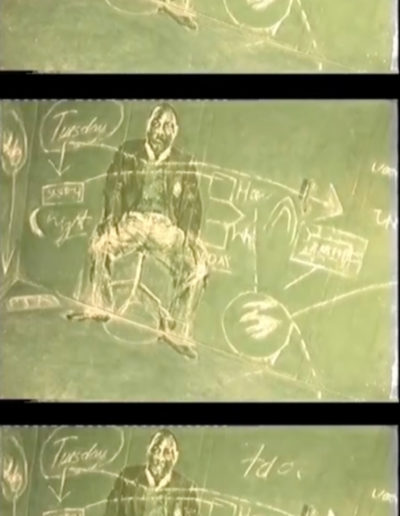

Jane Cheadle exhibited new drawings and presented two new animations in person: ‘Night Watchman’ and ‘Circles’.

‘Night Watchman’ is an animated film based on a reworked VHS recording made by the artist in the early 2000s. The film was inspired by a discussion with night watchmen in central Johannesburg and animates, in dreamlike fashion, their low-paid and uncertain jobs waiting out the night in quiet office blocks. The sequences, though cyclical, are transient still, much like Cheadle’s chalk drawings, which are erased and redrawn over and over.

‘Circles’ was performed and filmed in a near-deserted office building in an inner city, but this time the city is London, and the workers are the cleaning staff of a large agency. Many cleaning jobs have become more fragmented, lower paid and more precarious. The circles are ephemeral designs reminiscent of the movements of the staff. The animation brings out the meditative beauty of repetitive motions in slow mutation.

Hela Lamine performed ‘Travesée’, a reflection on migration, borders and group displacement. It is based on a survivor’s story of a shipwreck off the island of Kerkennah, in Tunisian waters. The boat was carrying migrants, 84 of whom died.

‘Traversée’ was played out in several cities (Sousse, Tunis and Paris) before coming to Geneva. Lamine explains, “It’s very important to me that at least these creations can move from place to place, ‘taunting’ borders, playing with and thwarting these invisible – but very real – limits, which both southern and northern policies can no longer manage.”

The participatory fresco entitled ‘ch9af el 7orrigua’, a key element of the performance, was started at the beginning of July in Sousse, Tunisia. The title is pronounced “chkaf el horrigua” and means ‘raft of the medusa’. It is an imaginative dialogue between Géricault’s eponymous painting and the mosaic of a medusa’s head in the Archaeological Museum of Sousse.

On each stage of its journey, the fresco will be redrawn with one fewer character, until none are left.

Nkoali Nawa grew up in the era of Apartheid and worked as a miner in his youth. At the time of South Africa’s transition to democracy, Nawa became an artist. His charcoal drawings and oil paintings depict life for the majority of South Africans: manual labour, family celebrations and Saturday shopping. Nawa’s realism, which is empathetic and expressive, brings him closer to his subjects.

The other artists are Cheikhou Bâ, Florine Demosthene, Stephan Erasmus, Siwa Mgoboza and Ledelle Moe.

DESIGN BY SEMAPHORE INTERNATIONAL | PHOTOS MARIANNE FOURIE